VIOLENCE

HUNGER

ILLNESS

DEATH

All contact with the camp SS was marked by violence. Hunger was a constant companion of the children and adolescents in the concentration camp. The catastrophic hygienic conditions led to an accumulation of diseases from which there was hardly any protection.

The children and adolescents lived in constant fear of death. They watched many people, including friends and relatives, die. Not only were they backward in their physical development due to hunger and diseases, they were also robbed of their childhood.

Gert Silberbard in an interview with David P. Boder in Geneva, August 27, 1946.

At the age of 16, Gert Silberbard was deported from Auschwitz to Buchenwald. In 1946, he vividly recalled being deprived of food and water after arriving at the Little Camp.

(„Voices of the Holocaust“, Illinois Institute of Technology)

MEALS FOR AN ENTIRE WORKDAY

8 a.m. - First breakfast

1 glass of hot milk with butter and honey

Roll with butter and ham

Roll with honey

Roll with jam or with something else

11 o'clock - Second breakfast

Pancakes with ham and scrambled eggs, rolled in breadcrumbs and fried in butter

Noodles au gratin with eggs, honey

and melted butter with rice fritters

Noodles with apples, butter and rolls

2 o'clock - Lunch

Clear soup (barley soup) made of chicken broth and breadcrumbs

or with fat dumplings

Stuffed beef with potatoes and paprika sauce

Italian pasta casserole with smoked sausage and tomatoes

Pierogi with liver

Dessert of semolina pudding with vanilla sauce

Fruit dessert, pudding from millet groats with jam

A glass of eggnog

17 o'clock - Supper

Asparagus in tomato sauce

Cauliflower fritters

Spätzle with butter and rolls

Stuffed peppers with tomato sauce

Potato pancakes with cream

The menu is unfinished. THERE’S AN ALARM AGAIN!

Dream menu for a whole working day by Maria Brzęcka, December 1944.

Maria Brzęcka, then 14 years old, put together her dream menu for when she was freed from the Meuselwitz labor camp. However, she could not remember the taste of most of the dishes and asked the women in her quarters to describe them to her. She couldn’t finish her list because of an air raid alert.

(Als Mädchen im KZ Meuselwitz. Erinnerungen von Maria Brzęcka-Kosk, Dresden 2016)

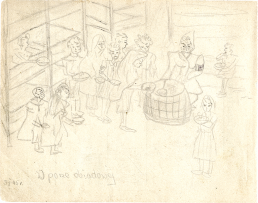

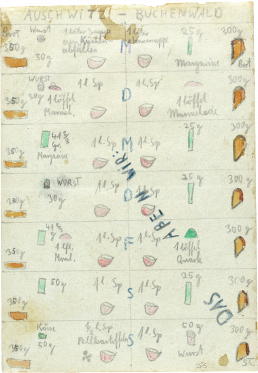

"This is what we ate." Drawing by Thomas Geve, 1945.

In his drawing, the 16-year-old compared the food rations in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, where he was liberated on 11 April 1945.

(Yad Vashem)

"So we handled heavy, toxic raw materials, picked everything up without protective gloves, no protective masks or aprons were required for us, we breathed in all the poisons and stood up to our knees in saltpeter. The locals called us "lemons" because our skin was so discolored."

Éva Pusztai-Fahidi recalls the deadly working conditions, 2011.

Éva Fahidi, who was deported from Hungary as a teenager, was a forced laborer in the Münchmühle subcamp. The working conditions in the munitions factory were murderous, and the prisoners could not protect themselves from hazardous substances because there was no protective clothing for them.

(Éva Fahidi, The Soul of Things, University of Toronto Press, 2020)

Plaster fresco from a barracks in the Ellrich-Juliushütte subcamp, made by Tanguy Tolila-Croissant in the fall of 1944.

Tanguy Tolila-Croissant was born in Paris on 16 October 1925. He began studying art at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts in Paris in 1942. In June 1944, he was arrested for resisting the German occupiers and deported to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in August, then to Ellrich-Juliushütte. There, he frescoed the walls in his block. Many similar pictures created by him have survived from the time before his arrest – with one difference: never is a dead tree to be seen. Tolila-Croissant died on 30 December 1944, at the age of 19.

(German Historical Museum)

Realms of Experience

PLAY

CONTACTS

FANTASY

HOPE

In order to escape the grim reality of life in the camp, which was characterized by violence and the fear of death, many children and young people tried to create a world using their fantasy or by playing games. Some also created fantasy worlds through drawing.

For the children and young people who had been deported to the concentration camp alone, contact with fellow prisoners was essential to maintain the will to survive. The young prisoners gave each other hope and comfort. Contacts with adult prisoner functionaries with influence were also essential for survival.

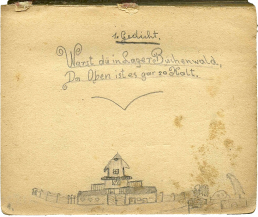

"Warst du im Lager Buchenwald, da oben ist es gar so kalt" (If you were in the Buchenwald camp, it's so cold up there). Poem and drawing by Johann Stojka, 26 February 1945.

The 15-year-old Rom was deported from Auschwitz to Buchenwald with his brother in the summer of 1944. He recorded his experiences with verses and drawings in a notebook. His poem ends on a hopeful note with the words, “We’ll get out after all.” The two brothers were the only members of their family to survive.

(Kazerne Dossin, Mechelen)

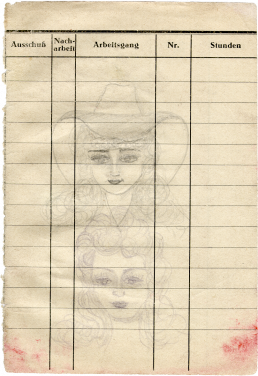

Drawing by Maria Brzęcka from the Meuselwitz subcamp, 1944/45.

To escape the reality of the Meuselwitz women’s camp, Maria Brzęcka, then 14 years old, drew. Using a small pencil and old inspection slips from the factory where she had to do forced labor, Maria created her “own dream world.” She drew scenes from life before the war, which she had older fellow prisoners describe to her. She also made drawings of extravagant female figures, many of which have been preserved.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

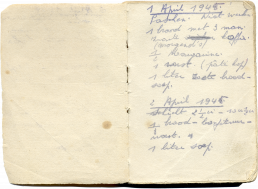

Diary of Leopold Claessens, 1-2 April 1945.

Secretly keeping diaries or notes was also a strategy of self-preservation and survival. The Belgian teenager Leopold Claessens was deported to the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp as a political prisoner at the age of 19. In April 1945, he survived an evacuation transport to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp. He started the diary in Bergen-Belsen, writing in retrospect, and recorded what he was given to eat

(private property)

Flowers for Bread. Franz Rosenbach in an interview with the USC Shoah Foundation, 23 October 1998.

The Sinto Franz Rosenbach arrived at Mittelbau-Dora when he was 17. In the camp, hunger was a constant companion. To supplement his meager bread ration, he began picking flowers in his free time and exchanging them with the block elder for bread. Contact with the privileged prisoner functionaries could be essential for survival.

(Visual History Archive)

"With Daddy at the Zoo." Camp commander Karl Otto Koch with his son Artwin at the Buchenwald zoo, October 1939.

In 1938, the SS built a zoo on the Ettersberg. It served as a recreational facility for the SS and their families. While opportunities to play were limited for the children suffering in the camp, the children of the SS personnel amused themselves at the zoo just outside the camp fence.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"Humor was an essential part of our mental resistance. And this mental resistance was, in short, a necessity for having the will to live. I tell you this as an ex-prisoner. No matter how rarely it occurred, how sporadically or how spontaneously, it was of great importance. Of very great importance!"

Humor as a means of survival. Felicija Karay in an interview, c. 2000.

From July 1944 to April 1945, 17-year-old Felicija Schächter (married name Karay) worked as a forced laborer for HASAG Leipzig. In an interview with psychologist Chaya Ostrower, she described humor as a means of mental resistance.

(Chaya Ostrower: It Kept Us Alive. Humor in the Holocaust, Wiesbaden 2018).

"Hasag is our father,

The best father there is!

He promises us

Long years of happiness,

Chorus:

The command’s for

Law and order, no more!

That we calm our nerves

Before we become

A can of preserves […]

HASAG Hymn. Prisoners’ humorous song, before 1945.

The women and girls who worked as forced laborers in the HASAG Leipzig subcamp wrote a humorous anthem, which they often sang together. It satirized the conditions in the camp.

Felicija Karay: Hasag Leipzig Slave Labour Camp for Women: The Struggle for Survival, Told by the Women and Their Poetry, Vallentine Mitchell & Co Ltd, 2003).

Scene from the fairy tale Snow White. Plaster fresco by French prisoner Georges Sanchidrian in the Ellrich-Juliushütte subcamp, 1944.

Georges Sanchidrian made colored murals on the plastered walls in Block 4 of the Mittelbau-Dora subcamp. Some frescoes with fairy tale scenes survived. Both adults and juvenile prisoners were housed in the block. Sanchidrian (born 1905) died on a death march in April 1945.

(German Historical Museum)

Realms of Experience

FRIENDSHIP SIBLINGS PARENTS

In order to survive, children and adolescents in the camps needed the help of friends, family members or adult fellow prisoners. Especially for the children, bonds with other people were important in order not to lose the will to live. Relationships helped with the procurement of food and clothing. It could be life-saving to be assigned to a lighter work detail with the help of prisoner functionaries.

Most of the children and adolescents came to Buchenwald or Mittelbau-Dora alone. Only a few were accompanied by their parents or siblings. Some suffered the loss of their relatives in the camps.

"And down here I will write the date when I will see my dear and beloved mother and father again in health". Excerpt from the notes of Alex Hacker, 10 February 1945.

In his secret diary kept during his imprisonment in the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp, Alex Hacker prepared an entry for the day of his return home, leaving a blank for the date. He was finally able to fill it in when he returned to his hometown of Budapest on 28 August 1945.

(private property)

Ludwig Hamburger:

The only good thing was, we didn't lose heart.

David Boder:

You didn't lose heart - how did that happen?

Ludwig Hamburger:

I always had my parents in mind [...] How I was a child [...] you have to stay brave and I always heard my mother and thought of my mother.

Ludwig Hamburger in an interview with David P. Boder, 28 August 1946.

Ludwig Hamburger was born in Katowice (Poland) in 1927. He and other young people from Katowice were deported to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp in 1941. In the winter of 1944, the SS sent him on a death march to Buchenwald. After the camp was liberated, he travelled on an aid transport to a Displaced Persons Camp in Geneva, Switzerland, where David Boder interviewed him in 1946. The last time he saw his mother was in 1941.

(„Voices of the Holocaust“, Illinois Institute of Technology)

Naftali Fürst (left) and his brother Shmuel in Bratislava, 1936.

The brothers Naftali and Shmuel Fürst arrived at Buchenwald from Auschwitz in January 1945. Prisoner functionaries saw that both boys were housed and protected in Children’s Block 66 in the Little Camp. Naftali was liberated there on April 11, while his brother Schmuel was sent by the SS on a death march and not liberated until early May 1945. The brothers reunited in Bratislava in the summer of 1945.

(private property)

"I always say that in the camps the easiest thing was to die, give up and die. The hard thing was to keep going and fight. And there we had to fight for our lives and every step was a struggle. And I can also say, I am convinced that because we were two brothers together, that helped us a lot. To be alone, a ten- or eleven-year- old child, I don’t think I could do that, because that would be terrible. We were dead tired, dead hungry, wet, you can't imagine."

Naftali Fürst in an interview in Haifa, 2009.

The two brothers Naftali and Shmuel Fürst survived the death march from Auschwitz Concentration Camp to Buchenwald in the winter of 1945 under the most adverse conditions. The brothers’ bond helped them in their struggle for survival.

(erinnern.at)

Friendship in the concentration camp: Ludwig Hamburger interviewed by David P. Boder, 26 August 1946.

Ludwig Hamburger and his friend survived a death march from the Auschwitz Concentration Camp to Buchenwald, where they were liberated. They subsequently went to Switzerland together.

(„Voices of the Holocaust“, Illinois Institute of Technology)

Liberated Jewish children in Buchenwald, 20 April 1945.

Second from the right in the second row is Markus Milstein. His brother Shraga was taken to Bergen-Belsen in January 1945 and liberated there. The Milstein brothers, like other boys in the photo, were from Piotrków Trybunalski and stayed together as a group in Buchenwald. The group included Israel Meir Lau (front row, second from right). He was the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of the State of Israel from 1993 to 2003.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"I was part of the group. I was never really alone, and it helped because we had a common fate." Account by Shraga Milstein, February 2021.

In the interview, he mentions the photo from Buchenwald showing his liberated brother Markus.

(Buchenwald Memorial)

"There was this boy … and I become a little bit friendly with him, you know? This was end of ’42. End of ’44, or January 1945, when I go to this Kinder barrack in Buchenwald, the boy is there. I recognize him, you know? And he recognizes me. This is almost two years later. … The first thing he does, he takes out half of his bread and gives me. And you know, a piece of bread in Buchenwald, I can tell you is like life."

Piece of bread. Jack Aizenberg in an interview with the USC Shoah Foundation, 8 July 1997.

Jack Aizenberg was deported to Buchenwald as a 16-year-old in the winter of 1944. After liberation, he emigrated to Manchester, England, where he was placed in a home with other former Buchenwald prisoners. For some time he also lived there with his friend Pinchas Koronitz, whom he had met in Buchenwald.

(Visual History Archive)