Return home

The liberated children and adolescents wanted nothing more than to return home to their families. For many survivors, however, that was impossible. Jewish survivors had often lost all their relatives in the Holocaust, and their hometowns had been obliterated. Reports of pogroms in Poland and Eastern Europe discouraged people from returning.

Many of the children and young people did not know where their relatives were or whether they were still alive. The Allies and aid organizations such as the Red Cross helped to reunite families.

Those who were able to return home the quickest were the young people from Western Europe who had been deported to the camps as political prisoners. Many were back with their families by early May 1945. They were considered heroes of the Résistance and were received with public honors in their home communities.

"By mid-May [1945], most of the prisoners whose health had been restored had left for their home countries. But there were exceptions: the Spaniards whom Franco had turned over to the Nazis preferred to remain in exile rather than return to a country still in the hands of a dictator. Many of the Poles were uncertain about the policies and new borders of their reborn state and therefore wanted to wait for further developments. Surviving Jews from Poland, Hungary and Romania feared returning to countries whose recent past had been marked by the horrific consequences of anti-Semitism."

Thomas Geve on the problems of returning home after liberation, 2000.

In his autobiographical account, Thomas Geve describes the impossibilities of returning home, especially for Eastern European Jews.

(Thomas Geve, Aufbrüche. Weiterleben nach Auschwitz, Constance 2000)

Western European prisoners leaving Bergen-Hohne barracks by truck, 25 April 1945.

In April 1945, evacuation transports from Mittelbau-Dora were sent to the Bergen-Hohne barracks, part of the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp complex. British troops liberated the survivors on 15 April 1945. Ten days later, the first liberated prisoners from France, Belgium and the Netherlands were able to return home.

(IWM)

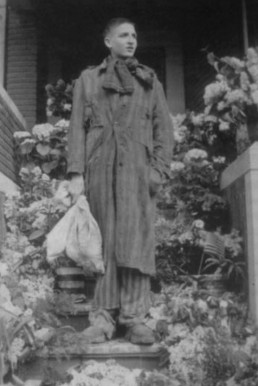

Roger De Coster on the day after his return to his hometown near Antwerp, 29 April 1945.

Roger De Coster was deported in 1944 at the age of 16 as a political prisoner to Buchenwald and from there to Mittelbau-Dora, together with his older brothers and his father. He was one of the liberated prisoners who started their return journey home from Bergen-Hohne on 25 April 1945. The day after his return home, he had himself photographed with numerous bouquets of flowers that had been presented to him on his return.

(Private property De Coster family)

"Saturday we were welcomed everywhere in Belgium. We arrived in Mol about four o'clock in the afternoon, where they took very good care of us. I left there with the Persoons family, who had come to pick up Jules Persoons, and arrived home around midnight, where everyone was waiting impatiently for Daddy, Willy, François, and me. The reunion was, of course, very emotional for me, and it was very joyful. I asked about Daddy and Willy [...]. Eight days later, I learned that my father had died on May 2 in a hospital in Weimar. François was still alive. He arrived in Paris and was home on June 9. I was the first from my village to return, but eight days later I got typhoid fever and just barely escaped death. Fortunately, after a few weeks I was back on my feet and a new life began for me."

Roger De Coster's account of his return home on 28 April 1945, c. 1991.

(François and Roger De Coster, Van Breendonk naar Ellrich-Dora, Berchem 2006).

Return of a Nacht-und-Nebel prisoner. Charles Brusselairs in prisoner's clothing after liberation, 1945/46.

Charles Brusselairs was arrested in 1943 at the age of 18 for resisting the German occupiers in Belgium. He was deported to Germany on the basis of the clandestine Nacht-und-Nebel-Erlass (Night-and-Fog directive). After spending time in various prisons, he arrived at Buchenwald in February 1945. The SS drove him on a death march to Theresienstadt in early April. There, he was liberated four weeks later by Soviet soldiers. After months in sanatoriums, he returned to his family in Belgium in 1946.

(Private property)

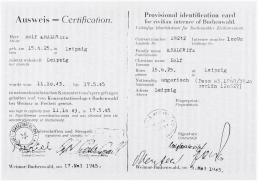

Rolf Kralovitz’ provisional identity card, 5 and 17 May 1945.

The US Army issued Rolf Kralovitz a provisional identity card in Buchenwald. On 17 May 17, he was officially released and could return to his hometown of Leipzig. The document also noted the time of his imprisonment in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

(Estate of Rolf Kralovitz)

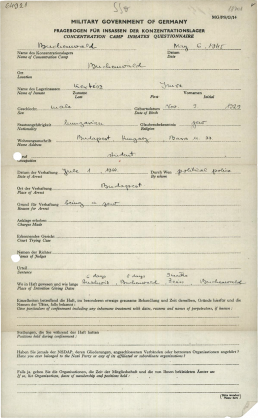

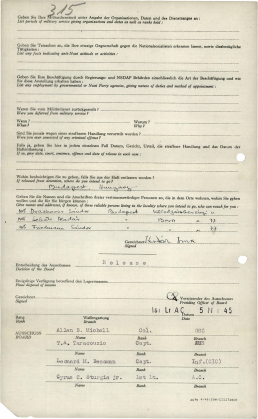

Questionnaire for concentration camp prisoners, filled out by Imre Kertész, 6 May 1945.

Imre Kerstész was born in Budapest (Hungary) in 1929. In July 1944, the police arrested him, and he was deported to Buchenwald via Auschwitz. After his liberation by the US Army, he filled out a questionnaire. As the reason for his imprisonment, he succinctly noted “being a Jew.” Another question asked, “Where do you intend to go if you are released from prison?” The 15-year-old entered “Budapest, Hungary”.

(Arolsen Archives)

"After a few steps I recognized our building. [...] On our floor, I rang our doorbell. [...] The door opened a crack, and a yellow, bony face of a strange middle-aged woman looked at me. She asked who I was looking for, and I said to her that I lived here. 'No,' she said, 'this is where we live,' and was about to close the door again, but she couldn't because I had put my foot in the door. I tried to explain to her that it was a mistake, because it was from here that I had left [...]."

In his story, the future Nobel laureate in Literature described his autobiographically-inspired protagonist's return home to Budapest and the conflicts it entailed, 1975.

(Imre Kertész, Fatelessness)

After liberation

Buchenwald DP camp and Kibbutz

In the course of World War II, the Germans deported several million people to the German Reich.

Children’s transports after the liberation

The parents and other relatives of the approximately 900 underage survivors of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp had almost all been murdered. Other orphans were brought to Buchenwald from…